on the philosophy of rating systems

We encounter rating systems on such a frequent basis that we do not stop to consider their philosophical implications. I do not mean the political questions of how much we should be influenced by them, or the technological question of how to produce reccomendations based on them, but the fundamental questions of what makes an appropriate rating system and how the rational users should rate objects they consume.

What axioms should a rating system satisfy?

Reviews are a manner by which consumers can express their opinions on objects they have consumed. While reviews can be generally informal, in the sense that they do not adhere to a particular form, a rating system is a formal framework for reviews. Popular examples are the N-Star Rating System, the like/dislike system, the out-of-N rating system, multi-scale rating sytem, and the like-button rating system.

A rating system is a formal framework, and therefore is a lossy representation of the users opinion of the object. We are forced to consider how the user’s opinions/feelings on the object and the rating of the object are related. Looking at the most popular rating systems, we notice that all of them are discrete bounded linear orders. In this light, we can consider the following axiom that we may want our rating systems to satisfy:

If the user rates object $x$ higher than object $y$, then the user believes that $x$ is superior to $y$.

(For now, we will consider the ratings of several different objects given by the same user. We will consider the complication of having multiple users in a moment. We will also set aside the question of what it means for the user to believe that an object is superior to another.)

There are several questions this interpretation raises:

- If the user has rated two objects equal, what should we infer about the user’s opinion of the objects? One possibility is that the user is indifferent about the objects. The other possibility is that the user things one of the object is superior to another, but her ratings do not reflect that. Our axiom does not really force one way or another. However, our intuition says that we would not like the scenario where the ratings are indifferent between the object, but the user isn’t.

- Most rating systems are bounded. For instance, in the 5-star rating system, the user can give no rating which is higher than 5 and no rating which is lower than 1. Consider what happens when our user gives some object $x$ a rating of 5 stars. This means that the user loses her ability to show that she values some object $y$ higher than $x$.

- The user must, at some point in time, rate her very first object $x$. Let us say that there is a collection of objects $Y$ that she will encounter in the future such that she feels that any $y \in Y$ is superior to $x$. Now, consider the information she can provide about her opinion on elements of $Y$ via the rating system. The possible structures are rather limited. How can the user possibly rate $x$ if she does not know anything about the objects in $Y$?

I can think of some alternate axioms that might do a better job.

The first one is a probabilistic version of what we discussed.

Suppose user rates objects $x_1, x_2, x_3, \ldots$, at time $t_1 < t_2 < t_3 < \ldots$. For a fixed $i$, consider the proposition $P_i$ that [the user has rated object $x_j$ higher than $x_i$ if and only if he believes that $x_j$ is better than $x_i$]. The higher $i$ is, the higher the probability that the proposition $P_i$ is true.

Another possibility is that we decide that the user’s opinion of objects and the ratings of the objects are connected in a somewhat weaker sense. In particular, there are certain emotional states that the object can put the user is in and the ratings map to the user’s emotional state. This is easiest to understand with the like/dislike system. By suggesting that the ratings map to emotional states rather than elements of some linear order, the above issues of determining how an user should rate something can be avoided. But this raises the question of how other people can infer information from the ratings of a particular user. Perhaps there is an axiom that relates the emotional states of the user to a more linear order like structure?

Alternative Rating Systems

As we observed in the previous section, in one way or another, all widely used rating systems are bounded discrete linear orders. Most of the objections we raised in the previous section are related to this fact. In this section, we consider some alternative possibilities for rating systems. Most of these are not commonly used. Perhaps, this is for good reasons of practicality and because we are not capable of mapping our mental states accurately into mathematical objects. Nonetheless, they make for an interesting philosophical discussion.

- Unbounded Discrete Linear Orders: This will be very likely represented using integers. The user gets to assign an integer to each object they want to rate.

- Dense Linear Orders: In this system, the user would instead represent their ratings using rational numbers. This way, she always has a chance of expressing the sentiment that she likes object $x$ better than object $y$ but worse than $z$.

- Permutations/Ranking: In this rating system, the user maintains a ranking of the objects she has rated. When she wants to rate a new object, she does a kind of sorted insert into the ranking. The difference between using a rational number to represent ratings and the permutation system is that the former allows for a kind of quantification.

- Partial Orders: So far, all the rating systems we have considered force the user to arrange their rated objects in some linear order. But perhaps, we can think of a rating system that allows for partial orders. This will allow us to express the user’s opinion of objects in a way that is more general than a linear order, in that she could say she is indifferent about the comparison between some objects. For instance, the user might be able to express a sentiment such as $x_1 \prec x_2 \prec x_3$ and $x_1 \prec y \prec x_3$ without having to say how she compares $x_2$ and $y$. A three star rating system would allow for three tiers, but one would be forced to put $y$ in a position that would determine its comparison with respect to $x_2$.

- Multiscale Rating: This is a specific instance of the partial order rating system. For example, a book reviewer might consider scales such as Plot, Characters, Writing and assign a rating to each of these scales, without having to say how she compares the scales.

- Scaled Like/Dislike: This is essentially a bounded dense linear order. Here, the user would assign a rating by picking a real number between -1 and 1. A version of this is actually already seen on instagram stories. People express their opinion by dragging the slider on an emoji.

Are there any interesting rating systems which are not related to some order theoretic structure? Consider Facebook’s reaction system for example: an user rates an object by choosing one of Like, Laugh, Angry, Sad, Wow. It is not clear how such a rating system can be considered a partial order at all. Perhaps, this system is more closely connected to the emotional axiomatization that we considered in the previous section.

Aggregating Ratings

So far, we have considered the role of rating system as a formal framework for expressing opinions. However, the most important component of a rating system is a mechanism that summarizes how objects have been rated by multiple users. For instance, in the like/dislike system, we see the ratings summarized by the number of likes and the number of dislikes. It is also common to summarize the star ratings by the number of average stars together with a histogram of the number of stars given.

In each of this scenarios, the aggregation mechanism always summarizes the data in a lossy manner. For example, in the case of the like/dislike system, one could potentially learn more information by knowing answer to this question: [If this object was liked by a person $x$, then what else did $x$ like?]. When we choose to summarize data, we have to understand the lossy nature of the aggregation and prioritize the information we want to our aggregation mechanism to present in the foreground.

Suppose a book reviewer has ratings for a book along the scales of Plot, Characters and Writing seperately. Should she consider an average of these scores? But what if she values one of these characteristics more than another? Is a weighted average of the scores more appropriate?

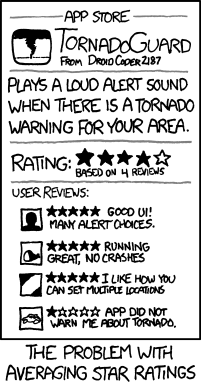

XKCD has several interesting comics critiquing rating systems. Here is one.

Some more can be seen in XKCD 1098 and XKCD 2329.

For the novel rating systems I discussed in the previous section, there are multiple issues with choosing an appropriate aggregation mechanism.

- Unbounded Discrete Linear Orders: If the users are attaching integers to the objects by themselves, how can we combine them? For example, suppose the ratings of one user is in the interval $[0, 100]$ and the other is in the interval $[-7, -1]$, is it fair to compare them? Should we normalize them before comparing them? What if the users are aware of one anothers ratings?

- Permutations: In the case of the ranking rating system that we proposed in the last section, we already know that it is impossible to device an aggregation mechanism that compiles the ranking of several users into a single ranking without creating problematic policies. This is the Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem.

- Partial Orders: One could combine partial orders by considering a lexicographic order. However, it is questionable whether this summary will be very useful.

Final Thoughts

This article can be summarized in two main points.

- A rating system is a formal framework that maps mental states about feelings for objects into ratings. Since mental states are complex, our formal framework should encompass a rich space of mathematical structures.

- Aggregating information from rich mathematical structures can be difficult.

However, in many cases, the existing rating systems are doing a great job of helping us understand which objects we desire. Perhaps, mental states are not as complex as we might think.